Un article (en Anglais) intéressant :

"Classic Tubes: Reynolds 753

Any fan of vintage racing and touring bikes is more than familiar with the familiar green, black and gold decal signifying Reynolds 531 tubing. Regardless of whether someone preferred Campagnolo, Simplex, Huret, Zeus, or whatever components for their bike, up until the 1980s Reynolds 531 was probably one of the most common elements of any high-quality lightweight bicycle. But in the 1970s, in a quest to reduce weight amid early experiments with titanium and carbon fiber bicycles, the Reynolds company introduced a new tubing that they hoped would give them the competitive edge and become the ultimate steel tubeset: 753.

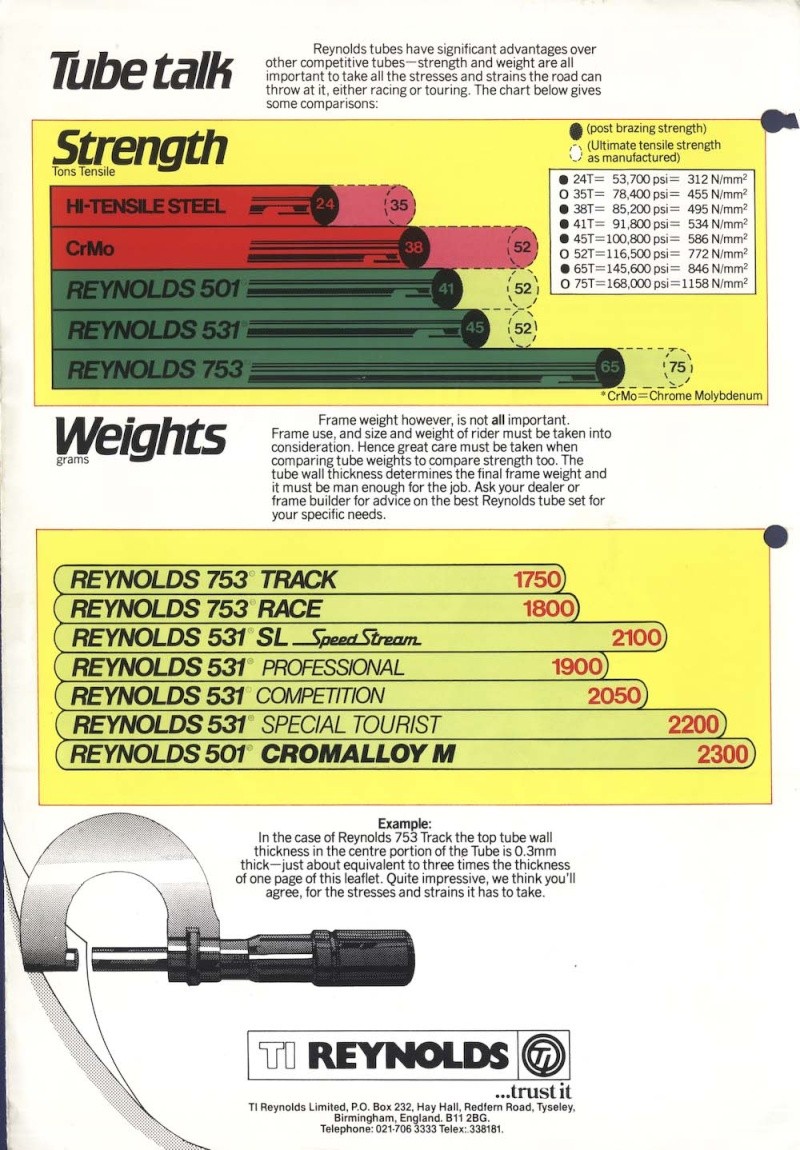

Reynolds 753 was essentially a heat-treated version of the company's familiar 531 manganese alloy steel. The heat treating boosted the tensile strength of the steel by about 50% and made it possible to draw the tubing much thinner than regular 531. Some versions of the tubing were drawn down as thin as 0.3mm in the center sections of butted tubes! It was claimed that the result could drop more than a pound from the weight of a bicycle frame without sacrificing strength.

Originally developed and tested in secret in the early '70s, Reynolds 753 was introduced to the public at the Paris Cycle Show in the Fall of 1975, but the company could already boast of a world championship (in the 5000m pursuit) and a new world record (50 mile time trial) with the tubing. The Raleigh racing team had raced in 1974 on 753 frames that were labeled as 531.

Although it was no longer a secret by 1976, it would take a couple of years before the general public would be able to get their hands on bikes built with the hot new tubing. Not surprisingly, the first company to offer it was Raleigh, which was at that time a wholly-owned subsidiary of TI Reynolds. But also, the tubing was not available or intended for mass production. Because of the need to preserve the strength gained in heat treating, low-temperature silver brazing was the only acceptable way to join 753 tubing, and this required very close tolerances for mitering and lug fit when building. Also, the tubing could not be cold set after brazing, so alignment had to be spot-on from the beginning. Because of the special care needed to ensure a proper build, any framebuilder who wanted to use it had to be certified by Reynolds. The certification process involved getting a sample tubeset, then brazing a frame which had to be sent to Reynolds for destructive testing. The inspectors would look for close mitering tolerances, good brazing penetration, and any signs of overheating in the joint and tubing. Only when certified could a builder be supplied with 753 tubing.

According to The Custom Bicycle by Kolin and de la Rosa (1979), by 1978 the only 753-certified builders in the U.K. were Raleigh, Bob Jackson, and Harry Quinn. Although not listed as such in the Kolin book, I know for a fact that Mercian was certified by '79. Jim Merz of Oregon and Proteus Design in Maryland were among the first certified builders in the USA, though many others would follow suit. In the US, I've heard that many builders took it as proof of their accomplishment and skill to be 753-certified, even if they never built more than a handful of frames with the material.

One interesting thing about 753 was that when it was first introduced, it was only available in metric dimension tubing. Metric dimensions were primarily used on French bikes at the time, while British, Italian, and most American custom-built bikes followed Imperial or fractional inch dimensions. For example, Imperial tubing dimensions were as follows: top tube, 1-in. (25.4mm); down-tube and seat-tube, 1 1/8-in. (28.6mm). French dimensions were: top tube, 26mm; down-tube and seat-tube, 28mm. I have not been able to find any explanation as to why the metric dimensions were used originally for 753. As I understand it, later versions of the tubing were made to Imperial dimensions, and would have been labeled 753R.

Not all 753 was drawn to ultra-thin walled gauges. Even from the beginning there were a couple of different gauges available. The thinnest was more common in smaller frames, while larger frames would normally have slightly thicker gauge tubes. The "cutoff" was likely somewhere around 58 or 59cm frame size - though that is not necessarily a universal fact. I've read arguments that individual builds might have taken the rider into account, so there could be exceptions where a larger frame might still have the thinner tubeset, or the other way around. If someone has an earlier-model 753 frame, one way to figure out which gauge tubing was used is to look at the seatpost size. A high-quality lightweight bike frame built with 531, or even Columbus SL tubing would normally take a 27.2mm seatpost, and in many cases (but not all), a smaller seatpost would indicate thicker-walled and heavier tubing. But most frames built with the metric-dimensioned 753 would require a 27mm seatpost. Larger frames would likely take a 26.8mm post.

So, how did they come up with the name for the new tubing? It's fairly well known that Reynolds 531 was named for the makeup of the alloy -- 5 parts manganese, 3 parts carbon, and 1 part molybdenum. It also had a tensile strength right around 53 tons/in². According to Tony Hadland's book Raleigh: Past and Presence of an Iconic Bicycle Brand, Reynolds 753 had a tensile strength of about 75 tons/in² and was drawn to .3mm in the center section of the tubes. Also, it was introduced in 1975, and the tubing was the result of their 3rd material tested.

Over the years, there would be variations on 753 released. In addition to the standard road set (later designated as 753R) there was a track tubeset which used the thinnest possible gauges (753T), a heavier-duty version for mountain and touring use (753ATB), and later still a slightly oversized diameter version (753OS).

Through the 1980s, bikes with 753 were something of a holy grail to some, and could be seen on some of the best professional racers' bikes. Bernard Hinault rode 753-tubed bikes for many of his professional wins, as did Greg LeMond as a member of the La Vie Claire team. Laurent Fignon's bikes in the '89 tour used it, too. Lots of pro teams did. But among the mere mortals, it always remained fairly uncommon. Price was always a concern. The fact that it could be pretty finicky to work with, and the certification process also kept it more exclusive. Still, there were a number of custom builders here in the U.S. who used it, and even some larger operations like Trek and Waterford built quite a few 753 frames. Even Rivendell, when it first was getting started in the 1990s, had their early bikes built by Waterford out of 753 (though I'm pretty sure it wasn't the super thin-walled versions).

Then, in 1995, twenty years after the introduction of 753, Reynolds introduced 853 -- an air-hardening alloy that had even more strength than 753 but did not require special handling or certification. More importantly, 853 could be welded, which by the '90s had become a much more common way to build bicycles. Two years later, the company introduced 725 heat-treated chrome-moly, which had a lot of the same physical properties of 753, but likewise required no certification and could be welded. Though I've read that a builder can still purchase 753, I doubt many bother since there are alternatives that are easier to work with. No, 753 was probably the top frame tubing a person could buy for its time, but that time is past. Still, for a classic bicycle fan, finding a vintage example is kind of a thrill. I'll come back to that again in future posts.

After the British, the French were seen as the most likely to use an ultra-light tubing like 753."

IL A PLUS DE CHEVEUX .... ca sent le crabe

IL A PLUS DE CHEVEUX .... ca sent le crabe

Belle bête en tout cas

Belle bête en tout cas